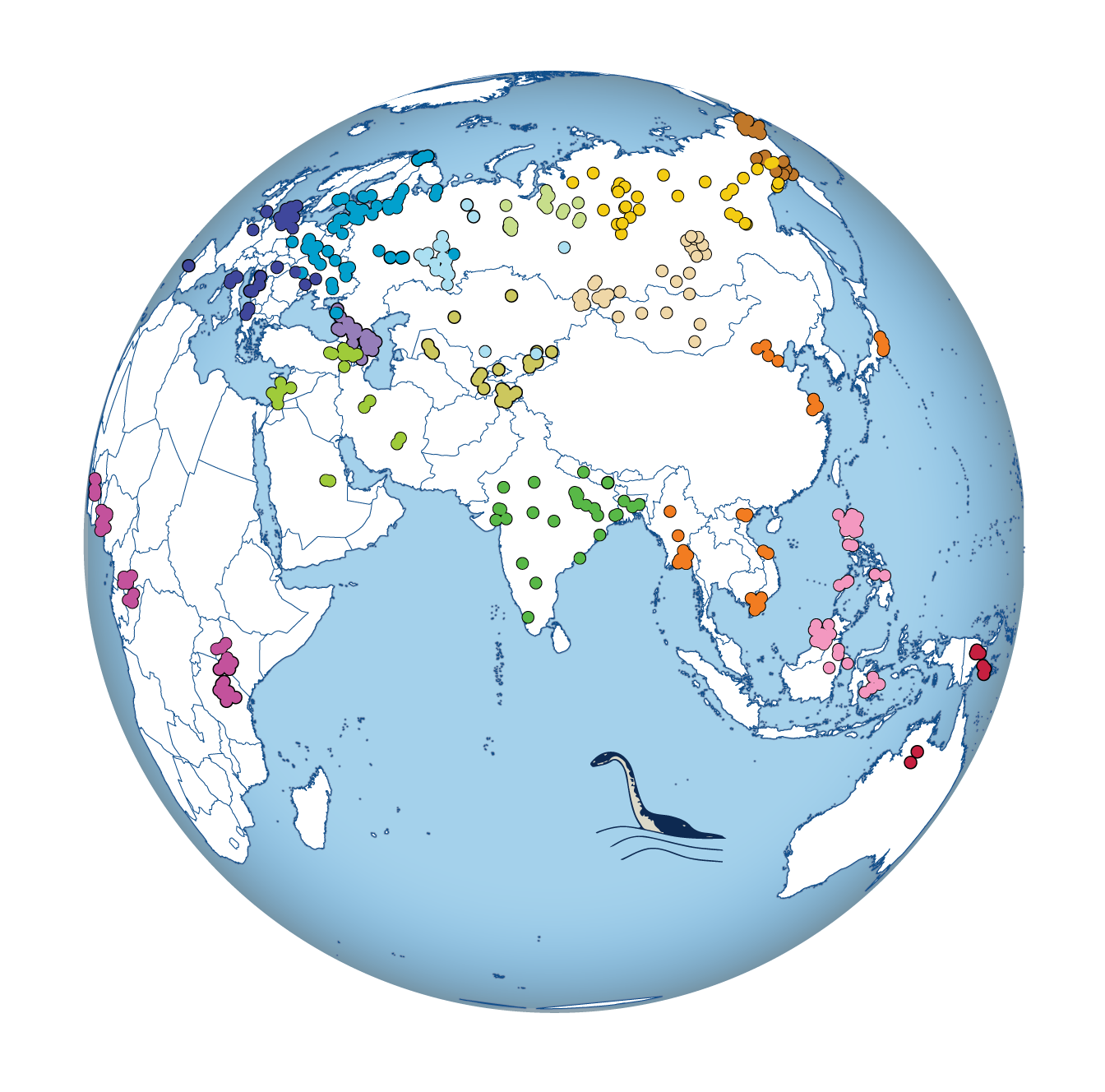

A new study in the journal Nature analyzes genomic diversity in 125 human populations at an unprecedented level of detail, tackling questions related to our species’ demographic history and dispersal out-of-Africa. The study is based on 379 high-resolution whole-genome sequences from across the world, generated by an international collaboration led by Mait Metspalu from the Estonian Biocentre, Estonia, and Toomas Kivisild from the University of Cambridge, U.K.

“This endeavor was uniquely made possible by the anonymous sample donors and the collaboration effort of nearly 100 researchers from 74 different research groups from all over the World,” Metspalu said.

The lab of Joseph Lachance in the School of Biological Sciences at Georgia Institute of Technology is one of these research groups. “By studying a global panel of individuals, we are able to identify genetic variants that are shared among different subsets of humanity and decipher our evolutionary past,” Lachance said.

The high geographic coverage of the samples permitted the researchers to study many aspects of genetic and phenotypic differences between individuals and populations using a common spatial framework. Researchers found that the sharpest genetic gradient in Eurasia separates East and West Eurasians. This barrier runs roughly along the Ural Mountains in the north, opens in the Steppe belt connecting Central Asia to South Siberia, and becomes strong again on the Tibetan plateau, elongating south toward the Indian Ocean while separating South and Southeast Asia.

In addition to increasing our understanding of the challenges that humans faced when settling down in ever-changing environments, the deluge of freely available data will serve as future starting point to further studies on the genetic history of modern and ancient human populations.

A. Maureen RouhiDirector of CommunicationsCollege of Sciences