In tough times, humans aren’t the only species that think twice about having children. Consider roundworm strain LSJ2.

Though it can’t think – much less think twice -- about anything, the laboratory worm underwent a surprising mutation that made it prioritize the survival of adults over creating abundant offspring. Researchers noticed the sweeping change in behavior, and the mutation, after LSJ2 had faced hardship for 50 years.

Such so-called life history trade-offs have been described in many living things from mice to elephants, but now, for the first known time, researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology have pinned some to a specific mutation.

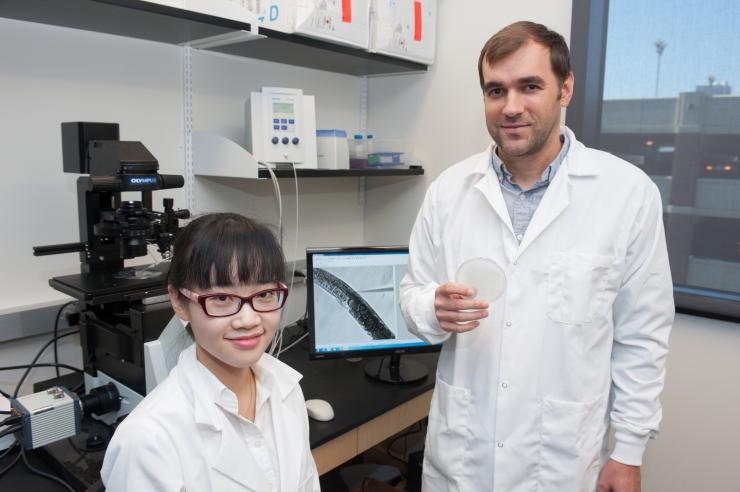

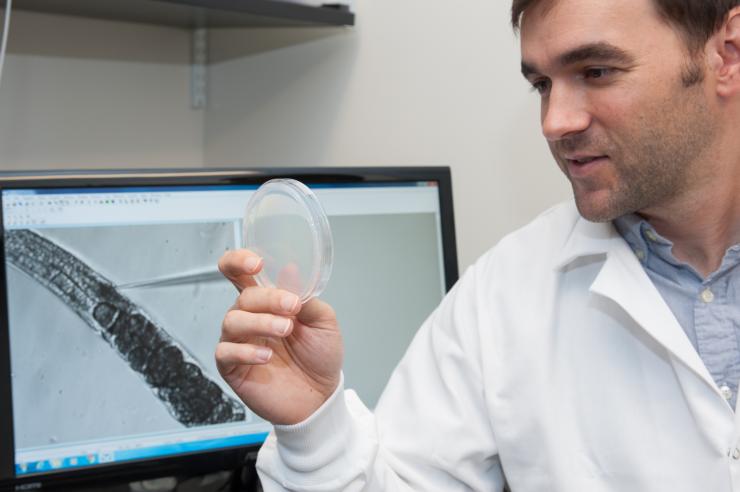

“This is a great hint at how life history trade-offs could be regulated genetically,” said lead researcher Patrick McGrath, an assistant professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Biological Sciences.

The researchers confirmed the link in LSJ2, a strain of the C. elegans species, by duplicating the mutation in another strain, which reproduced the mutation’s effects to a very high degree.

The researchers published their results in the journal PLOS Genetics on Thursday, July 28, 2016. Their work has been funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Ellison Medical Foundation.

Snowball to avalanche

The mutation in the LSJ2 strain amounted to a small deletion in its DNA. As a result, a large protein changed by a meager 10 of its roughly 3,000 amino acids.

But that triggered a huge behavioral overhaul that boosted lifespan and slowed down reproduction. The contrast between the minor genetic tweak and its transformative ramifications might compare well with a toddler knocking loose an avalanche with a snowball.

The new discovery also has a tangential connection to human genetics. The roundworm shares with us the NURF-1 gene, on which the mutation occurred. And an associated human protein is involved in, among other things, reproduction.

Evolve faster, please

All at once, LSJ2 did a lot of peculiar things, and that got the attention of McGrath and his team. And that’s what the lab roundworms are there for.

Since 1951, generations of scientists have been speeding up the evolution of lab-bound C. elegans by forcing the microscopic species of roundworms to adapt to new, mostly stressful, conditions. Then, when researchers have noticed changes, they’ve worked to trace them to the animals’ genes.

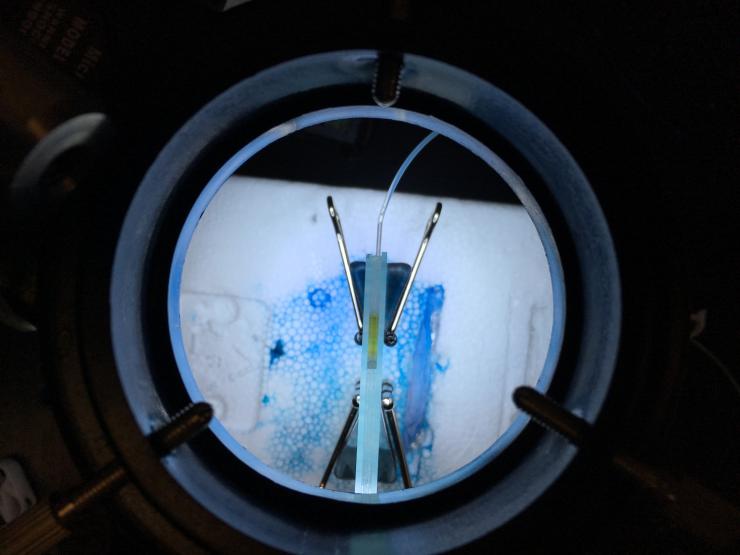

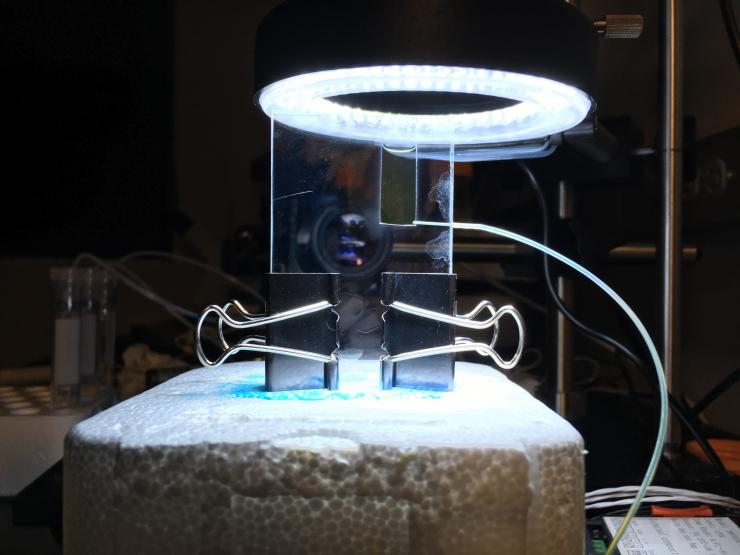

McGrath points to a thin, glass slide standing vertically under a light with tubules of fluid connected to it. Inside the slide, is a different lab strain of C. elegans.

“We’re raising those in fluid with gravity pulling them down to see if mutations will give them the ability to swim,” McGrath said.

50 years of bread and water

In the case of LSJ2, researchers came up with a different challenge to accelerate its evolution. They fed it bland food for 50 years.

“It’s a diet of watery soy extract with some beef liver extract,” said Wen Xu, a graduate student who researches with McGrath. Sounds yucky enough to humans, but to the roundworm, it's worse. It equates to a regimen of bread and water.

Mutations eventually took hold to promote LSJ2’s survival in the scanty broth, and they were head-turning.

Fewer kids, less sleep

“The stark thing that we noticed first was the propensity to no longer enter the state called dauer,” McGrath said. It’s a kind of hyper-hibernation. “Dauer is something most C. elegans do to extend their lives, but LSJ2 did not. And it lived longer in spite of it.”

Then the list of anomalies grew, and grew.

“We found that almost everything was affected – when they started reproducing, how many offspring they made, how long they lived,” McGrath said. Some even survived exposure to drugs and heavy metals.

“Eventually we realized that the worms were prioritizing individual survival over reproductive rate.”

Mutation sleuthing

In many species, sex dries up when food is scarce, resulting in fewer progeny to compete for it. In addition, many organisms are well-equipped to manage their energies to survive dearth.

But C. elegans LSJ2 had to mutate into those abilities, and so many mutation-based behavioral changes all at once is uncommon.

“What you usually find is mutations that play narrow, very specific roles,” McGrath said. “They only affect egg laying, or they only affect life span, or they only affect dauer formation."

McGrath and Xu went sleuthing for DNA alterations by mapping quantitative trait loci, which matches up changes in characteristics to genetic changes. They dug in for a long investigation, anticipating multiple suspects among LSJ2’s many mutations.

“There were hundreds of genetic differences between roundworm strain LSJ2 and the one we were comparing it to,” McGrath said.

‘Smoking gun’

The comparison laboratory strain is called N2, and it has led a pampered existence with a diet of E. coli -- optimal food for C. elegans. (Both the E. coli and the roundworms are strains that are not harmful to humans.)

So, N2 hadn’t been pushed to mutate so much. In addition, to avoid confusion in their research results, the researchers reset some of the mutations N2 did happen to undergo.

The comparison led to swift evidence in LSJ2. “Every single time, it pointed us to the same genetic region on the right arm of chromosome 2,” McGrath said. C. elegans has six chromosomes.

“There were only five genes that were candidates. One of the mutations was a smoking gun -- a 60-base-pair deletion just at the end of the NURF-1 gene.”

NURF-1 has the function of remodeling chromatin, which pairs DNA with proteins to wrap them into chromosomes. The resulting configurations strongly influence which genes are expressed. It appears the tiny mutation in the remodeling gene may have led to a massive change in the expression of other genes.

There are missing pieces needed to understand the pathway from the mutated gene to the massive real-life changes, and the researchers are working to fill them in.

Worm whoopy

To confirm the mutation as the trigger of the changes, Xu deployed a CRISPR Cas9 gene editor into N2 worms to make the deletion that LSJ2 had received via mutation, and the results left little doubt.

“It had a lot of the same effects – longer life, dauer formation,” Xu said. “The main difference was the reduction of reproduction rates. It was only about half as much in the comparison worm that got the gene editing.”

By the way, as sex goes, C. elegans are mostly hermaphrodites that produce eggs and their own sperm to fertilize them with. But there are also males that copulate with the hermaphrodites to add new sperm and with it genetic diversity.

Edward E. Large, Yuehui Zhao and Lijiang Long from Georgia Tech; Shannon Brady and Erik Andersen from Northwestern University, and Rebecca Butcher from the University of Florida coauthored the paper. Research was sponsored by grants from the National Institutes of Health (numbers R21AG050304 and R01GM114170) and by an Ellison Medical Foundation New Scholar in Aging grant.

Writer and contact: Ben BrumfieldResearch News(404) 660-1408