The 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded jointly to James P. Allison and Tasuku Honjo for their discovery of cancer therapy by putting the brakes on the immune system. Allison is a professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, in Houston. Honjo is a professor at Kyoto University.

The 2018 winners “found ways to alert immune cells to recognize cancer cells as non-self and destroy them,” says Francesca Storici, a professor in the School of Biological Sciences and a member of the Parker H. Petit Institute for Bioengineering and Bioscience (IBB). Working with both healthy and cancer cells, she studies what happens inside cells and the DNA damage that occurs with cancer. “Research in this direction has the potential to save many lives not only from cancer but possibly also from many other cell degenerative disorders,” Storici says.

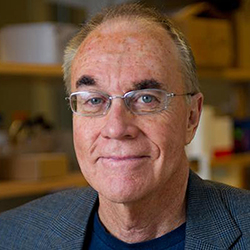

The immune system is well-designed to attack cells that the body considers foreign. The system is tightly regulated to avoid attacking our own normal healthy cells. “This year's winners are long-time students of the mechanisms underlying this regulatory aspect of immune function,” says John McDonald, a professor in the School of Biological Sciences whose lab uses an integrated systems approach to the study of cancer. He directs the Integrated Cancer Research Center at Georgia Tech and is a member of IBB.

Most cancer cells are sufficiently mutated to be viewed as “foreign.” But they often escape attack by shrouding themselves with proteins that block the immune response. By developing strategies to inhibit these blocking mechanisms, McDonald says, the Nobel Prize winners “unleashed the natural anti-cancer properties of the immune system.”

Specifically, Allison and Honjo unraveled the mechanisms that inhibit T-cells, the major immune system components that attack foreign cells, says Fredrik Vannberg, an assistant professor in the School of Biological Sciences and IBB member.

Their basic science discovery led to what is now known as immune checkpoint therapy, which works by reversing T-cell inhibition and allowing the body’s own immune system to destroy cancer cells. Immune checkpoint therapy has saved the lives of many late-stage cancer patients, Vannberg says.

However, not every patient benefits from any particular therapy. Research at Georgia Tech aims to provide additional tools to find the treatment that suits the patient. For example, McDonald and Vannberg collaborate in using genomic profiling to help predict which specific therapy will lead to the best clinical outcome for a given cancer patient.

Toward this goal, last year they offered to cancer researchers – for free – a new program that predicts cancer drug effectiveness via machine learning and raw genetic data. They hoped to attract other researchers who will share their cancer and computer expertise and data to improve upon the program and save more lives together.

“The hope is that – by exploiting these new discoveries alone and in combination with other novel strategies to target treatment to tumors – cancer will soon be transformed from a lethal to a manageable chronic disease,” McDonald says.

A. Maureen Rouhi, Ph.D.Director of CommunicationsCollege of Sciences