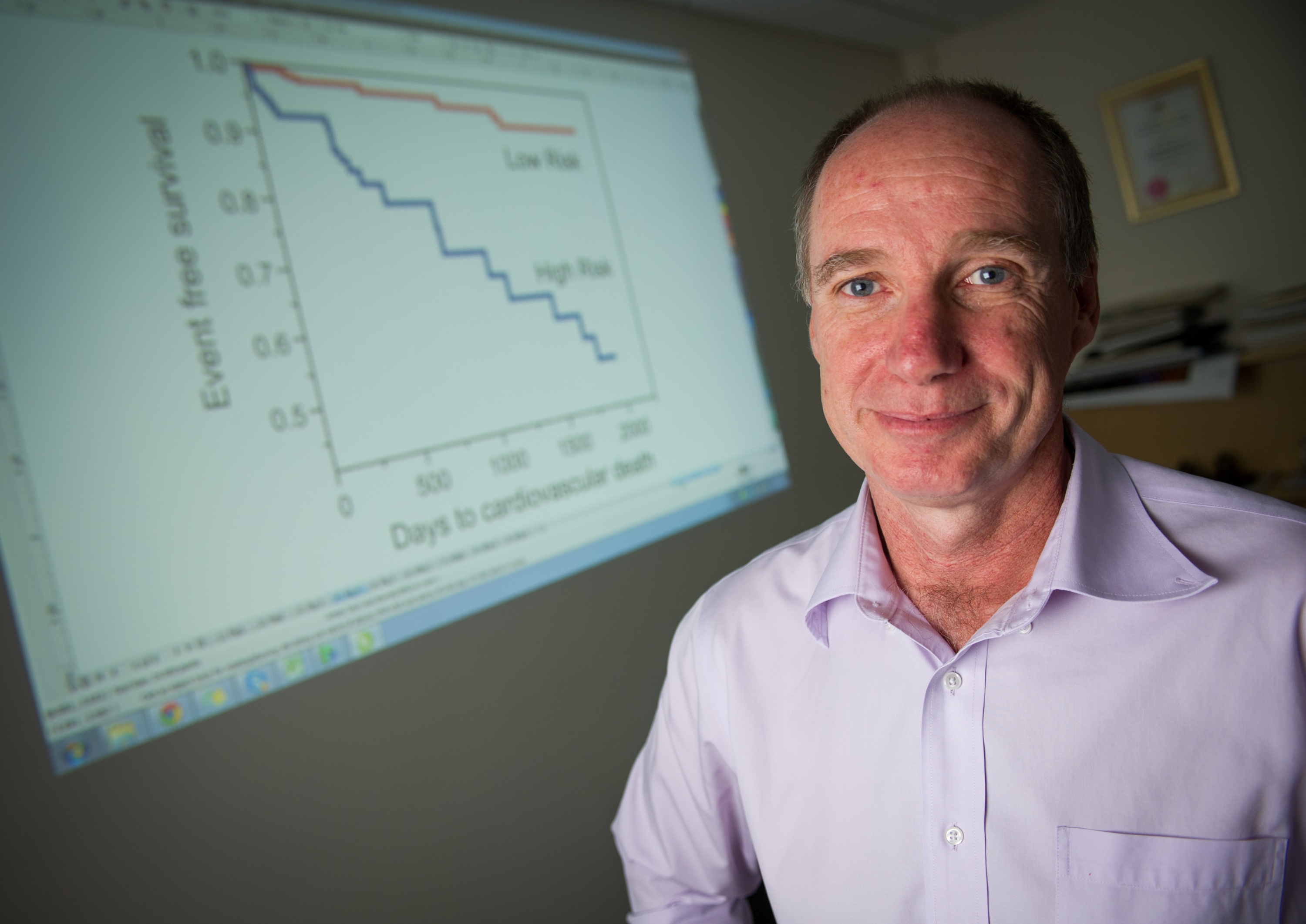

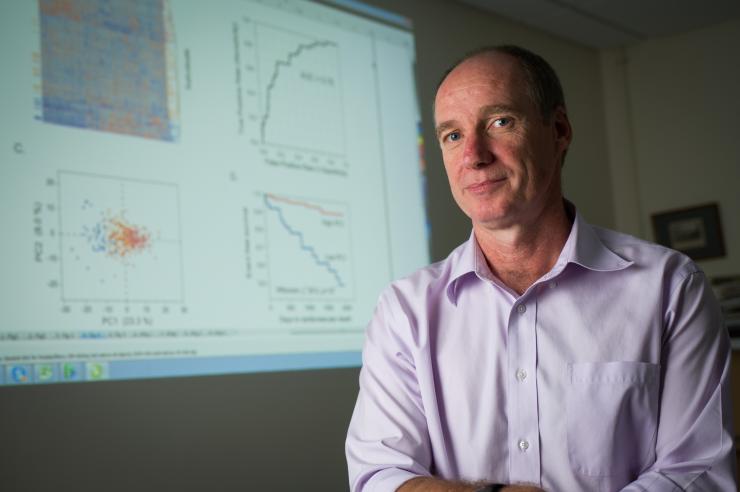

The lab of Greg Gibson at the Georgia Institute of Technology has been awarded a grant of $2.3 million to study the subtle genetic underpinnings of autoimmune-related diseases by taking a computational approach.

The National Institutes of Health made the award as part of an $11.1 million total investment in research funds slated for five institutions, including Georgia Tech. The researchers’ work could increase understanding of the causes of diabetes, Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, forms of heart disease, and more afflictions where inflammation is at issue, and where there may be a connection to autoimmunity.

"We know that hundreds of genes impact autoimmunity, but the challenge is to narrow down the actual DNA sequence changes that have an impact. This grant combines our statistical genetics expertise with evolutionary genetics and genome editing by collaborators,” said Greg Gibson, a professor at Georgia Tech’s School of Biological Sciences.

In its research, Georgia Tech will work together with Rice University in Houston and Temple University in Philadelphia. Gibson's researchers will handle statistical analysis and interpretation; Rice's scientists will carry out gene editing, and evolutionary geneticists at Temple will contribute insights on which gene sites should or should not be variable in the human genome.

Attacking friends: Autoimmunity

Our cells work together with masses of microbes that are an integral part of the human body, but the immune systems of people with related diseases can attack the microbes and healthy human cells, and lead to inflammation. “Lymphocytes, for example, could be attacking the body,” Gibson said.

“We’re looking at genes that regulate the immune system,” he said. “They’ve all got subtle effects. What counts is that they all work together. We’re looking for sections of genetic code that work a little oddly.”

Researchers will put data through algorithms to better identify genetic variants in sections of the human genome that do not encode proteins, but have regulatory functions, the NIH said in a news release. These are sections of DNA that, for example, turn encoding genes on and off.

Subtleties multiplied: Susceptibility

They have been lesser studied but are known to be critical and could provide new information on yet undiscovered pathways composed of multiple faint characteristics that add up to disease.

"Taken alone, some small characteristic may appear indistinct, and at the same time, it’s really hard to read how a big group of them work in total,” Gibson said. “But their cumulative effect is dramatic, and unfortunate.”

Recent genomic research methods have compared the complete genomes of patients with diseases to those without them, leading to thousands of statistical hints. Now new data and interpretive approaches are needed to effectively sift through these to see the foundations of diseases, or make predictions of who is most at risk, and what people can do to reduce the risk.

The NIH hopes statistical methods will allow prediction of possible effects some variants have on susceptibility to disease and on drug response. The funding comes from the NIH’s National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI)'s Non-Coding Variants Program, and the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Writer and contact: Ben BrumfieldResearch News(404) 660-1408