Researchers experimenting with live zebrafish witnessed a 200% increase in the strength of intestinal contractions soon after the organisms were exposed to the cholera-causing bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The strong contractions led to expulsion of native gut bacteria.

The discovery, detailed in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, “was remarkable and unexpected,” the authors write.

The researchers – from the University of Oregon, Georgia Institute of Technology, and Memorial-Sloan Kettering Cancer Center – used genetic manipulation and cutting-edge three-dimensional microscopy to monitor what happens when the disease-causing microbe is initially introduced into the larvae of zebrafish, an organism commonly studied as a model for understanding health and disease in vertebrates, including humans.

The multidisciplinary team of physicists, molecular biologists, and microbiologists focused on the harpoon-like injection capabilities of the type VI secretion system. This appendage, found in many bacteria including Vibrio cholerae, transfers toxic proteins into competing healthy cells.

The scientists engineered Vibrio cholerae mutants with variations in that secretion system and then observed the behavior of the microbes as they invaded zebrafish colonized with Aeromonas veronii, a native species in that animal’s gut.

SWIFT ACTION

Instead of simply killing native Aeromonas gut bacteria upon contact, as expected, when Vibrio cholerae entered the gut the native bacteria were swiftly flushed out.

“The secretion system induced dramatic increases in the strength of the peristalsis process, the contractions that move gut contents down the gastrointestinal tract much like squeezing a tube of toothpaste from the end to the top,” says coauthor Brian K. Hammer, a microbiologist and associate professor in the School of Biological Sciences at Georgia Tech.

The researchers hypothesized that the unexpected bacterial manipulation in the digestive system might be driven by a particular piece of the type VI machinery known to bind to actin, a cellular scaffolding protein. When the scientists deleted the actin-binding domain from the bacterial gene, they saw that Vibrio cholerae lost its ability to enhance peristalsis and its ability to expel native Aeromonas.

The findings shed new light on how the waterborne Vibrio cholerae functions. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Vibrio cholerae triggers more than 3 million cases of acute diarrheal illness and 100,000 deaths in people worldwide each year.

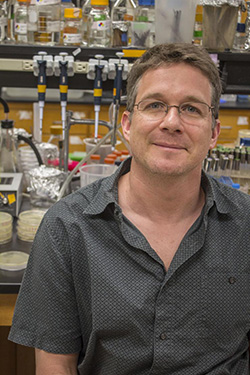

“Knowing the strategies by which the bacterium is able to invade the intestine can open doors to therapies that might disrupt these paths,” says corresponding author Raghuveer Parthasarathy, a professor of physics at the University of Oregon, whose imaging and analysis techniques were used in the study.

Because the type VI secretion system is also found in native gut bacteria, including those in the human gut microbiome, it could be harnessed for therapies, including specially designed probiotics, to promote beneficial species or to defend against disease invasion, Hammer says.

“We suspect that other gut microbes, both pathogenic and beneficial, might similarly make use of this secretion system to reshape their environment,” Parthasarathy says.

Most previous research on this secretion system has relied on studying bacteria outside of animals – on a Petri dish for example, or by examining fecal samples – to infer what is happening in the gut during infection.

While the research team captured the impact of invasion by Vibrio cholerae, understanding just how it takes root in the host, such as what specific cells in the animal are targeted, is an open question, Parthasarathy says.

“We still have no idea how the action of his secretion system’s harpoon is causing the changes in the muscle contractions,” Hammer says. “We suspect that what we are observing may be an immune response to irritation in the gut lining. But what cells in the gut are being poked?”

How the findings may reflect the colonization of Vibrio cholerae in humans is not known, but the role of the secretion system makes a similar result plausible, the researchers wrote in their conclusion.

BIRTH OF COLLABORATION

The findings emerged from a collaboration born in 2015 when Hammer, Parthasarathy, and coauthor Joao Xavier, a researcher at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, discussed joint research possibilities during a conference, Scialog: Molecules Come to Life, in Tucson, Arizona.

The Scialog (Science and Dialog) was organized by the Research Corporation for Science Advancement and sponsored jointly with the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, with additional support from the Simons Foundation. The goal of Scialog is to rapidly catalyze new interdisciplinary collaborative teams, such as the one formed by Hammer, Parthasarathy, and Xavier, to work on high-risk, high-reward projects.

As a result, their three labs received an award from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Simons Foundation to pursue their Scialog idea. The National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust, and Kavli Microbiome Ideas Challenge also supported the research.

PHOTO CAPTION

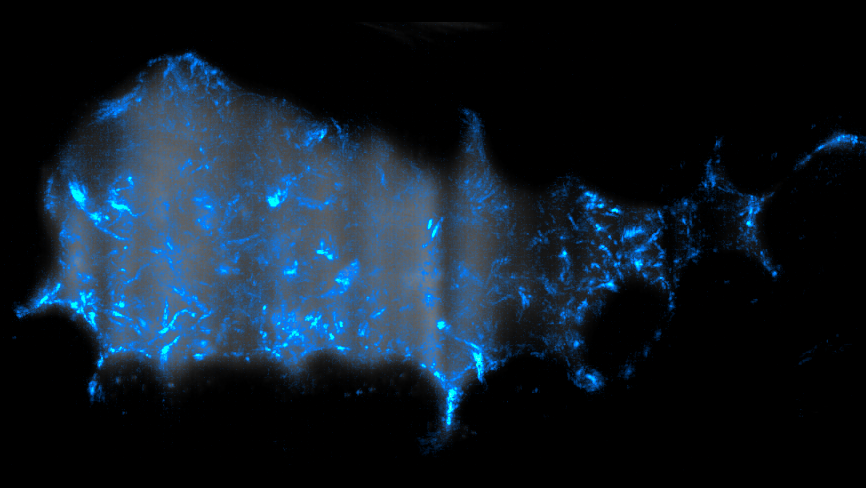

Trajectories of Vibrio cholerae bacteria (blue) swimming inside the gut of a larval zebrafish. The gut is visible as a gray background. The total duration of the movie that was “squashed” into this image is 3.5 seconds, and the total image width is about 0.3 mm. (Courtesy of Raghuveer Parthasarathy)

A. Maureen Rouhi, Ph.D.Director of CommunicationsCollege of Sciences